Part One: The Golden Peacock

The air on top of the Sinjar mountains can get nippy in the month of October, especially late in the day, when the sun begins to sink on the horizon, allowing the temperature to drop below 60 degrees Fahrenheit. Rising to a height of 4,800 feet, the 62-mile-long mountain range looms over the desert of northwester Iraq like a massive monolith. The mountain range and its surrounding environs is home to the Yazidi, a Kurdish people who trace their origins back to Biblical times, claiming to be created directly from Adam, as opposed to the rest of humanity, who were born of Eve. The Yazidi also practice one of the most unique and complex religions in the world today, a monotheistic belief system which combines ancient Kurdish and Persian beliefs with the three Abrahamic faiths (Judaism, Christianity, and Islam) that was founded in the 12th century by the Sufi Muslim Sheikh Adi.

In late October 1993, I found myself on the top of Sinjar Mountain. I was leading a large team of United Nations weapons inspectors on a major inspection which had as its primary mission the discovery of locations in Iraq believed by the CIA to have been involved in the hiding of SCUD missiles the United Nations had been tasked with accounting for in their entirety, ensuring that they had all been either destroyed, dismantled, or rendered harmless in accordance with the provisions of relevant Security Council resolutions. The Iraqis had fired some 49 SCUD missiles at targets inside Israel during the 1991 Gulf War, perhaps better known as Operation Desert Storm. I had played a role in a failed effort to interdict the Iraqi SCUD missiles before they could be launched—the Iraqis were able to hit Israel up until the last days of the war without suffering a single loss.

After the war concluded, the United Nations created a Special Commission tasked with overseeing Iraq’s disarmament of its chemical, biological, nuclear, and long-range ballistic missile programs, collectively referred to as weapons of mass destruction, or WMD. I had served as a member of the Special Commission since September 1991, and at the time of the Sinjar operation had served on ten inspections, all of which were focused on the SCUD missile accounting issue. We were in Sinjar because, in the closing days of Operation Desert Storm, CIA paramilitary operatives deployed in nearby Syria, using long-range optics, reported seeing convoys of trucks believed to be carrying SCUD missiles, drive into tunnels carved into the base of the mountain. My job was to locate these tunnels and inspect them to see if they still contained missiles, or evidence of missiles having been stored there.

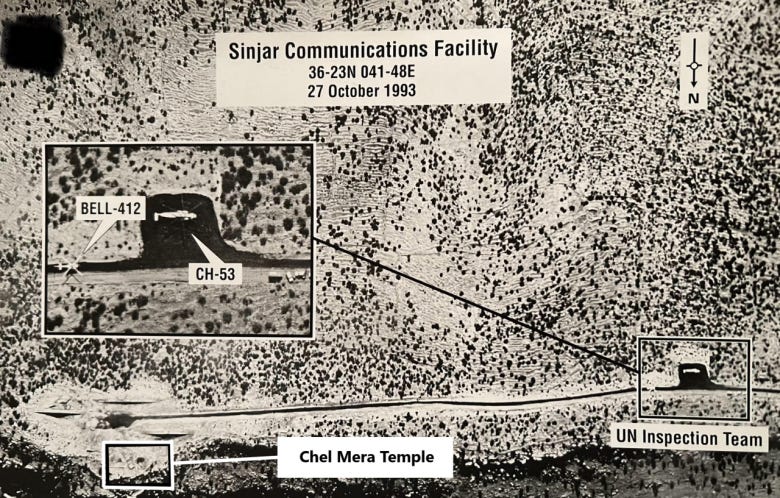

The team I assembled was the largest in the history of the United Nations disarmament effort in Iraq—more than 75 persons drawn from more than a dozen nations—including elite special forces from the United States, UK, and France. The team also included members of the CIA paramilitary team that had observed the suspicious truck convoys, and a helicopter detachment flown by aircrew from the US Army’s ultra-secret Flight Concepts Division, responsible for flying deniable covert missions around the world. Supporting a team of this size was a challenge, so I enlisted the help of the German Air Force detachment that flew in support of the UN weapons inspection effort. The operation around Sinjar was scheduled to take several days, so I set up a command-and-control center on top of Sinjar Mountain, which doubled as an expeditionary helicopter landing zone, accommodating the German CH-53 and American Bell-412 helicopters.

Midway through the Sinjar Mountain inspection, I found myself with time on my hands. The ground teams which had surrounded the mountain were putting in for the night, having established observations posts that would enable them to monitor any movement around the mountain using night vision optics. The Bell-412 helicopters flown by the pilots from Flight Concepts Division were being outfitted with forward-looking infra-red (FLIR) pods, which would enable them to flight night observation missions around the mountain and respond to any suspicious activity the ground teams might detect.

After making sure all teams had reported in, and the helicopter crews had finished their preparations, I decided to take a walk toward an abandoned Iraqi military communications facility situated to the east of the UN airstrip. Pre-inspection studies of aerial imagery had revealed the existence of a Yazidi temple which, upon further investigation, was found to be named Chel Mara, or “Forty Men,” in honor of the bodies of 40 Yazidi men said to be buried on the temple grounds.

Music has been an important part of my life’s journey, and looking back on six decades of experience, I often find myself linking specific events to a soundtrack that plays in my mind whenever the memories come flooding back. This linkage is not created post-facto, but rather from the moment of inception; that is, the song that was playing in my mind at the time of the event became the soundtrack.

As I approached the entrance to the Chel Mera Temple, the cool wind kicking up the dust from where my boots struck the ground, I was overtaken by the sound of drums beating ominously, followed by a cacophony of shouts, grunts, and other utterances, before Mick Jagger’s voice exploded in my head:

Please allow me to introduce myself

I’m a man of wealth and taste

I’ve been around for a long, long years

Stole many a man’s soul and faith

The linkage between the classic Rolling Stone’s song, Sympathy for the Devil, and my exploration of the Chel Mera Temple, was no accident or coincidence: I was approaching a place of worship, where the Yazidi people would come to pray to Tawûsî Melek, the “Peacock Angel,” whom the Yazidi believe to be the leader of the seven angels created by God who was cast down to earth in the form of a peacock to confront and vanquish the forces of evil.

According to the Yazidi, Tawûsî Melek was ordered by God to bow down and worship Adam, since Adam was God’s creation. Tawûsî Melek refused this order, stating that he, Tawûsî Melek, was God’s original creation, born of eternal light, unlike Adam, who could be reduced to dust. Because of his impudence, Tawûsî Melek was cast into Hell, where he resided for 40,000 years, until his tears extinguished the fires of his underworld prison, an act which reconciled him with God. From the perspective of the Yazidi faithful, Tawûsî Melek had passed God’s test, and in doing so, was revealed as an obedient and devoted follower of God, void of sin, and as such the perfect intermediary between mankind and the divine.

As I stepped over the threshold of the temple, entering the structure, I was struck by the presence of dozens of pieces of red, green, purple, and yellow silk cloth suspended from the ceiling. The Yazidi offer prayers to Tawûsî Melek so that he might convey their message to God. These prayers are made in private, inside the sanctuary of the temple, and manifest themselves in the form of a knot that is tied on pieces of silk which hang suspended from the roof of the temple. The Yazidi, when offering a prayer, would tie a knot in the silk, “capturing” their prayer, and then untie a knot left by another, thereby “releasing” it so that their prayer could be answered.

The Yazidi community had just finished celebrating their annual “Feast of the Assembly” holiday, which takes place between October 6 and 13. The Yazidi of Sinjar made an annual pilgrimage during this time to the nearby tomb of Sheikh Adi located in Lalish, a valley situated just north of the town of Shekhan and considered to be the holiest place in the Yazidi faith. My visit to the Chel Mera Temple came some two weeks after the conclusion of this holiday.

Inside, there was evidence of recent human activity, including the presence of offerings of food, water, and flowers laid throughout the room. The air smelled of incense, some of which was still smoldering in stone receptacles, and the light from oil lamps cast eerie, flickering shadows across the dome ceiling, darkened by years of accumulation of soot.

My head brushed into the silk hanging down from the ceiling, and I could feel the knotted cloth as it contacted my face. I touched the suspended material, feeling its texture in my hand, before my fingers closed in on one of the knots. For a moment, I toyed with the idea of making a wish myself and tying a knot. But as I reached up my other hand to carry out this task, Mick Jagger’s voice once again intruded into my mind:

Pleased to meet you

Hope you guess my name

I released the silk, suddenly overcome by a dark panic. Backing away from the burning incense, lighted lamps, and the urns carrying the various offerings to Tawûsî Melek, I got to the entrance, where I pivoted, tripped on the raised sill located there, and stumbled out of the structure, the sweat on my face immediately chilled in the cool breeze that wafted across the mountain top. I looked down at my hand, and noticed it was trembling.

“You idiot,” I said to myself. “You almost offered a prayer to the Devil.”

Tawûsî Melek is no ordinary angel. And his story is not unique to the Yazidi. In the Bible, one can find reference to the angel “born of eternal light” in Isaiah 14:12: “How you are fallen from heaven, O shining one, son of the morning! How you are cut down to the ground, You who weakened the nations!”

Early Christians shared some of the foundational beliefs regarding Tawûsî Melek, believing he had fallen from the grace of God due to his association with humans. However, rather than seeing Tawûsî Melek as a defender of humankind, the early Christians believed the fallen angel envied humans, as evidenced by his refusal to prostrate himself before Adam, his pride in loving himself more than others manifesting itself in hatred for the happiness of others.

Saint Augustine of Hippo, second only to Paul of Tarsus in terms of influencing the dogma and doctrine of the Catholic and Orthodox Christian Churches, rejected the notion that Tawûsî Melek’s envy of Adam was the original sin, instead pointing to the angel’s free will in seeking to seize God’s throne to become God-like in the world of man.

I turned and looked back at the Chel Mera Temple, its white conical minaret framed in the setting sun. I was a Marine, and unaccustomed to the fear that had overtaken me. If I walked away, I thought to myself, I was surrendering to fear.

I walked back to the temple entrance, steeled myself, and stepped back inside, taking in my surroundings.

I focused on the silk cloth, and the knots they contained, each representing a separate conversation with Tawûsî Melek. I examined each on in detail, reflecting on the nature of the wishes one might ask of the “Peacock Angel.” It struck me that the requests would be similar of prayers offered by man to any deity—for health, for wealth, for happiness, for success. In many ways, these prayers echoed the temptations of Jesus, as detailed in Matthew 4:1-11. But the entity that tempted Jesus wasn’t Tawûsî Melek—or at least that is not what the bible named him.

He was the Devil, Satan…Lucifer.

Just as every cop is a criminal

And all the sinner’s saints

As heads is tails

Just call me Lucifer

‘Cause I’m in need of some restraint

My eyes probed deeper into the temple space, focusing on each piece of colored cloth and the knots they bore. As I scanned the walls, I settled in on something protruding from the wall. My eyes adjusted to the dim light, and soon the object revealed itself—a golden Peacock.

Tawûsî Melek.

Lucifer.

“I see you,” I thought to myself. “I know who you are.”

Lucifer reveals himself in many ways, some so subtle as to be indiscernible. As I stared at the golden Peacock, my mind began to drift to the inspection. It was the culmination of a year’s effort, my personal response to a US intelligence community which refused to accept the results of inspections carried out in the late summer-early fall of 1992 which proved, from my standpoint, that the UN inspection teams had accounted for the totality of Iraq’s SCUD missiles. Instead, the CIA claimed to have intelligence that Iraq had buried anywhere from 12-20 missiles in hide sites throughout western Iraq.

I responded by coming up with an inspection concept of operations which incorporated ground penetrating radars mounted on helicopters. The United Nations, I said, was prepared to investigate the US intelligence claims, but first the US had to provide the radars. Several million dollars later, we had assembled an inspection team which included the Bell 412 helicopters, with bulky ground penetrating radars attached, flown by the pilots from the Flight Concept Division.

The audacity of my plan caught the attention of the Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC), home to both Delta Force and Flight Concepts Division, and the CIA’s Special Activities Staff, the paramilitary arm of the CIA’s covert operations division. JSOC was heavily involved in investigating the fate of Navy Lieutenant Commander Scott Speicher, who had been shot down over western Iraq on the first night of Operation Desert Storm. Initially believed to have been killed because of the shootdown, Speicher was later reclassified as missing in action. Some Qatari hunters claimed to have found wreckage of an aircraft that was in the vicinity where Speicher’s plane had gone down. Some of the suspected buried missile sites contained in the CIA intelligence were located near where the Qatari hunters spotted the wreckage, and JSOC debated briefing me on the intelligence and seeing it I would be willing to modify the inspection to permit Delta operatives embedded with the UN inspection to peel off and inspect the suspected wreckage site.

The CIA wanted to take advantage of the team I had built to investigate the Sinjar targets. This I readily agreed to. They also proposed that we use the unique capabilities contained in the team to conduct a surprise inspection of a facility in downtown Baghdad which, at the time of the proposed inspection, would have been hosting an emergency meeting of the Presidential committee assigned the task of hiding weapons of mass destruction from the UN inspectors. I had taken this proposal to the Executive Chairman of the Special Commission, a Swedish diplomat named Rolf Ekéus, who tentatively approved the plan pending more specific intelligence. In the end, the Secretary of State, Warren Christopher, balked at the plan, which he likened to an act of war.

Both JSOC and the CIA were very pleased with how the inspection was unfolding. We had not found any evidence of buried missiles, but it appeared as if the US had known that would be the outcome. Instead, we had inserted into Iraq the equivalent of a joint special operations task force which provided the US with a wide array of operational and intelligence-related options in dealing with a recalcitrant Iraq.

The JSOC/CIA plans did not mesh at all with the mandate of the United Nations inspection teams. But they could not bear fruit unless they were able to operate under the cover provided by the UN inspection teams. This is where I came in—I was being treated as their “inside guy,” the trusted associate who could “make things happen.”

It was an ego boost, to say the least. I was at the center of the universe when it came to resolving the most important US foreign and national security problem facing America at the time—Saddam Hussein’s Iraq. And I was being offered a seat at the table where I would play a critical role in planning and implementing the operations that would assist the US in solving this problem.

I was already being approached by the Flight Concepts Division pilots, who asked me to come up with inspection concepts where they could play a role. And a senior CIA Special Activities Staff operator was likewise grooming me for future inspection missions that made use of his personnel. The key to both opportunities was the need to sustain the notion of a non-compliant Iraq still believed to be armed with undeclared SCUD missiles.

All I had to do was file a report saying that the inspection mission was unable to adequately investigate the issue of hidden missiles, and that there was a need for more aggressive follow-on inspections. I had developed a good reputation within the United Nations as a capable inspector who remained loyal to the mission of the inspection teams and the Charter of the United Nations. This reputation, combined with the full support of the US government for whatever ideas I might come up with, would guarantee continued access to Iraq by JSOC commandos and CIA paramilitary operatives, who would be carrying out mission tasks totally unrelated to the mandate of the inspection teams.

Both JSOC and the CIA reminded me that I was an American first and foremost, and that there was no shame in violating a non-binding pledge to the United Nations to serve the national security interests of my country.

The “America first” argument was very persuasive—too persuasive, in fact. I was leaning toward going along with the JSOC/CIA plan. But there was one small fact that kept nagging at me—when I first joined the UN weapons inspection team, back in September 1991, I had traveled to Washington, DC, for a meeting with an interagency team comprising the State Department, the Department of Defense, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the Defense Intelligence Agency, and the CIA. The purpose of the meeting was to set forth the “rules of the game,” so to speak, when it came to my work. I wanted the US government to commit to my mandate—did I work for the United Nations, or did I take orders from the US?

I was told in no uncertain terms that my job was to faithfully fulfill the mandate set forth under relevant Security Council resolutions.

And I had, up until the Sinjar inspection, assiduously remained true to that tasking.

But now I was being asked by my government to deviate from that undertaking.

To violate a pledge I had made to the UN and myself.

In the name of national security.

These thoughts were racing through my mind as I fixed my gaze on the golden Peacock.

You’re an American, a voice sounded in my head. Whether it was my own, or that of someone else—a CIA officer, JSOC operator…or Lucifer—I couldn’t say.

I gave my word, I countered in a voice that was less resolute.

You have no future at the United Nations, the voice announced, this time sounding like a senior UN administrator, who told me my aggressive style was incompatible with the staider culture of the international organization.

This is not a career, I responded. I have a job to do. Nothing more, nothing less.

You will be welcomed back with open arms, the voice cried out. There are great opportunities awaiting you.

I had no reply. I wanted so much to rejoin the community that had shaped my life in the decade leading up to my joining the United Nations. That experience defined me. I was an empty shell otherwise.

I am an American, I said to myself.

I am an American.

“Mr. Scott?”

My eyes broke contact with the golden Peacock, and I gathered my senses.

“Mr. Scott?” the voice repeated itself.

It was Karim, one of the Iraqi minders. He was outside the temple entrance, calling to me.

“I’m in here,” I replied.

“It is getting dark, Mr. Scott. It is not safe to be out here by yourself. We need to get back to the camp.”

The Sinjar Mountain region was home to Kurdish rebel groups opposed to the rule of Saddam Hussein. They had been fighting Iraqi authority for decades and had become emboldened following Iraq’s defeat in Operation Desert Storm. The inspection command post was collocated with an Iraqi Army camp whose soldiers were providing security for the inspection teams as they drove around the Sinjar massif.

I made my way to the exit, casting one last look at the golden Peacock.

Karim was an engineer who had spent many years working on the nascent Iraqi space program, building an indigenous satellite that Iraq had hoped to put into orbit using a space launch vehicle, the Al Abid, which used SCUD missile technology. The Al Abid exploded mid-air during its first and only test flight. Karim and the other engineers working on the project were transferred to Project 144, dedicated to modifying SCUD missiles for longer ranges. He worked there during Operation Desert Storm, supporting the Iraqi missile force as it squared off against a US-led coalition which had committed considerable resources to destroy Karim, the other Project 144 engineers, and the soldiers who operated the SCUD launchers.

I had been a part of that effort and had told Karim as much. He bore me no grudges and had emerged as one of the more forthright of the Iraqi escorts, trying hard to put the vast quantities of data the inspection team had collected into a proper perspective. In August 1992 I led an inspection of the Space Research Center, where Karim had worked. We uncovered a trove of documents that had been secreted away in the ceiling of one of the buildings. I treated the discovery as a “payday,” the hard-earned fruits of an intelligence-driven effort which had succeeded beyond our wildest expectations.

Karim laughed when he saw the documents. “These are not what you think they are,” he said. “These are my working papers. I don’t know why someone decided to hide them, but they contain nothing relevant to your work.”

Over the course of the next few days, Karim helped us make sense of our discovery, and by the end of the inspection I had come to accept his version of events. The US intelligence community had a different take, accusing me of accepting the Iraqi version without question. But they were not present during my conversations with Karim. There was nothing “soft” about my approach, and by the time we had finished, I had extracted more than enough fact-based information, linked to the very documents the CIA had tasked us with discovering.

Upon my return to the US, it became clear to me that what the US intelligence community resented the most was that I had exploited the documents outside of their span of control. They had plans for these documents, it seemed, which included breathing nefarious intent into their contents, and then leaking carefully picked information to the Security Council as a means of sustaining the American argument that Iraq was not complying with its obligation to disarm.

As it was, the US did use the documents to craft a narrative of Iraqi non-compliance which centered around intelligence reports about buried missiles. It was these reports which I sought to investigate with the ground-penetrating, radar-based inspections in the early fall of 1993, and which brought me to Sinjar Mountain and the Chel Mara Temple.

“You should not go in there, Mr. Scott,” Karim said as I exited the structure, looking at me disapprovingly.

“It is the place where Shaitan (Satan) resides. The Yazidi pray to him.”

We walked away from the temple. The sky had grown dark, and the stars were beginning to emerge in the evening sky.

“They are Devil worshippers.”

The wind had picked up, and I felt a shiver make its way down my spine. It could have been the chill of the night that produced this result.

Or it could have been the voice that continued to echo in my mind.

You are an American.

Do the right thing.

That night Karim and I rode on the FLIR-equipped Bell 412 helicopter, which had the task of flying security over the camps of the four inspection sub teams that had encircled Sinjar Mountain. I made radio contact with each sub team, making sure everything was in order. Afterwards, the Flight Concept Division pilots flew along the base of the massif, using the FLIR to investigate potential tunnel entrances carved into the mountain’s foundation.

We found none.

As we returned to the mountain air strip to put in for the night, the Bell 412 flew over the Chel Mara Temple site. The FLIR picked up the heat signature of Yazidi worshippers as they entered the temple to offer their prayers to the golden Peacock.

To Tawûsî Melek.

To Lucifer.

I see you, I said to myself, staring down at the temple.

I know who you are.

I know what you are trying to do.

I looked across to where Karim sat. He was staring at me. “Shaitan lives here, Mr. Scott,” he shouted over the sound of the helicopter rotors.

It was almost as if Karim knew about the voices in my head.

“Shaitan will offer you many temptations, Mr. Scott. But he is evil,” Karim shouted.

“He is evil.”

I returned to the UN Headquarters in New York, where I prepared my final report.

The Chief UN administrator tasked me with putting a budget together for the coming year. Weapons inspections were not cheap affairs, especially ones as large and complex as the missions I had been planning as of late.

This was my chance—I could lay the groundwork for a new round of confrontational inspections built around a core group of JSOC and CIA personnel simply by emphasizing that the results of the inspection were inconclusive, and that more intrusive inspections along the lines of the aborted raid on the Presidential committee responsible for hiding weapons of mass destruction.

You are an American.

Yes, I am, I replied. The US government instructed me to adhere to the mandate of the UN Security Council. That mandate was disarmament, not taking down the government of Saddam Hussein.

I am an American.

I am an American Marine.

And I will faithfully execute my orders to the best of my abilities.

“He is evil,” Karim had warned me.

But what’s puzzling you

Is the nature of my game

I know you, I said to the voice in my mind.

And I know your game.

The budget I submitted called for a transition away from confrontational inspections to missions linked to long-term monitoring of Iraqi industrial facilities.

The CIA and JSOC were not pleased.

On November 8, 1993, I was summoned to the Old Executive Office Building, part of the White House complex. The Director of the CIA (at that time, James Woolsey) maintained an office there, and I was tasked with providing him a briefing on the final post-inspection accounting of Iraq’s SCUD missile inventory. First, however, I had to navigate my way past twin gatekeepers appointed by Woolsey—Martin Indyk, the senior director of Near East and South Asian Affairs at the National Security Council, and Bruce Reidel, the National Intelligence Officer for Near East and South Asian Affairs at the National Intelligence Council. I provided Indyk and Reidel with a very detailed accounting of Iraq’s SCUD missile force, concluding as I had done a year prior that the United Nations had accounted for all of Iraq’s known SCUD inventory.

This was not the message James Woolsey wanted to hear. Both Indyk and Reidel thanked me for my briefing but told me that there would be no presentation for the Director. Charles Duelfer, the deputy executive chairman of the UN weapon inspection effort, accompanied Indyk and Reidel into the CIA Director’s office. Later, when Duelfer emerged, I was told that Woolsey dismissed my briefing and the underlying analysis behind its conclusion of Iraqi compliance.

“The official position of the CIA,” Woolsey told Duelfer, “is that Iraq retains an operational force of 12-20 SCUD missiles, and this number will never change, no matter what you do as inspectors.”

As Duelfer recounted his conversation with Woolsey to me later that day, I could hear Tawûsî Melek in my mind, mocking me.

You fool, he said, you could have had anything you desired. A door had been opened that led straight to the top of the national security apparatus of the United States. Woolsey had been waiting to anoint you as a key ally.

Now you are alone.

The golden Peacock was right—I was alone. The US government all but abandoned me, and the United Nations had likewise become nervous about the aggressive nature of my work. But I had remained true to myself and the principles and values that defined me as both an American and, more importantly, as a human.

And this was something that Tawûsî Melek, Lucifer, or Shaitan, could never take away from me.